We started the day with some catching up on journaling and photos, and then we walked with our host, Loisi, to the bakery that’s open on Sundays, and on to Michl and Silvia’s, now equipped with a dozen rolls and two “Topfenschmankerl”—a sweet baked good with a new name that is not translatable into English, and maybe not even into German (“Quark-Leckerbissen”?). We all had breakfast outside on their deck, even though we had some rain showers, snug and dry underneath their portable gazebo / garden tent structure. Silvia was recovering well from her shoulder surgery and had a great time; the conversation was an interesting mix of German and English. We sat until almost 11, and then Michl took Loisi home and us to the local papermaking museum. It’s located in a former paper factory, first founded in the 1870s and then modernized, before the operation moved into a completely new facility in the 2000s. Laakirchen has two paper factories, and Michl estimated that between those and some ancillary industries that emerged here, more than a third of the town, 3000-4000 people, work in the paper industry. We loved the exhibit and the surroundings, and learned a lot about paper making past and present. I didn’t realize for how long all paper was made from rags and that the process of extracting cellulose from wood wasn’t really discovered until the 19th century. Both processes require a lot of water, and that’s plentiful in Laakirchen, which has the Traun flow through it. We would have spent much more time there, but Michl called with new plans for the day, which required us to cut short our tour because we had a train to catch. He picked us up at noon, after only about half an hour at the old factory, and we drove to the nearby train station in Gmunden to catch a 12:15 train to Hallstatt, about an hour away. The route there was gorgeous—mountains and meadows left and right, cute little houses nestled along the edge of cliffs, and more lakes. It really felt like we were riding through a model train landscape, because it had all the classic features, even the short tunnels to cut through promontories. And then, when we got to our station, the train station is actually on the other side of the lake from Hallstatt, and we alongside a huge group of other tourists, many with full-size suitcases, piled into a boat that took us there in about 10 minutes—in the pouring rain, which conveniently stopped right as we were arriving at the Hallstatt dock.

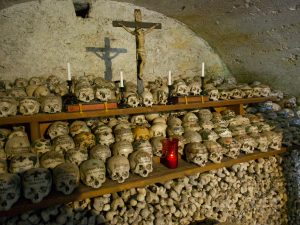

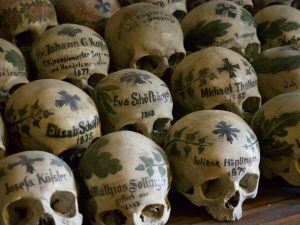

Hallstatt was a truly strange experience. It is a beautiful little town squeezed in between the mountains and the lake, with houses built right against the cliffs in multiple layers connected by staircases and winding paths. The traditional wood balconies and roofs with their gingerbread cutouts are very pretty, and every wall and balcony is covered with flowerpots and vines, roses blooming everywhere. There are two churches, one down in the village and one up high in the hills, and a classic market place, cobblestones, winding paths, docks for fishing boats—and the upper church, with its baroque triptych altarpiece, has a special feature, the Beinhaus or “bone house,” technically a charnel house. Because there is so little room between lake and granite cliff, the dead of the village were traditionally only buried for 15 years, then exhumed, and their skulls and some of their bones placed in the charnel house—with the gravediggers painting their names and life dates plus some decorative patterns on their skulls. There are 1,200 skulls in the Beinhaus, most of them painted, and it’s apparently unique in that you can see families of the dead arranged together in generations. Of course this is a tourist attraction, but so is the entire town—so much so that it was actually replicated in China as a housing development. That apparently pushed its fame level in China to the extreme, because the most heavily represented tourist group in the crowds were Chinese, and the quadrilingual tourist signs always included Chinese (and another alphabet I didn’t recognize). There was something implausibly pretty about the whole area, a sort of Disney effect that made it hard to remember that real people live in Hallstatt (and that some occasionally drive cars through the pedestrian-packed streets, obviously grumpy about not being able to barrel through to their destination). But we had gorgeous weather and loved our walk through the town, and we found a nice, not too expensive restaurant with a garden that had covering (there was still the occasional drop of rain), and had a light mean while looking out over the city. We also finally found some pet table cats, and the Beinhaus was obviously a huge hit. We did not go to the salt mines that were the start of this and so many other towns in this region, but they are high up above the town and they can be toured. That would be fun for another trip!

We headed back on the boat back to the train station at about 4 pm and then took the train back to Gmunden at 4:30. Again, the ride was lovely and with the clouds gone, we got a new view of the lakes and mountains around us. Michl met a former student on the train, and I got to overhear a lot more conversation in an Austrian dialect without having to pipe up and become part of it. We drove back home from Gmunden to Laakirchen and then just hung out with Silvia while Michl took their daughter and her boyfriend to the train station (they live in Graz and Vienna respectively). We ordered pizza from a local dive, and although some of it featured some odd ingredients for our taste (hard boiled eggs, “four cheeses” including feta and blue cheese), we had a nice (if late—9 pm!) dinner and talked about traveling and about the differences between houses in the US and houses in Austria. It was a very nice wrap-up to the day and to our visit, and we crashed at about 11 after Michl took us back to Loisi’s.