For 11/23/2021, to p.1146

Scene: On the Smolensk Road as the French retreat

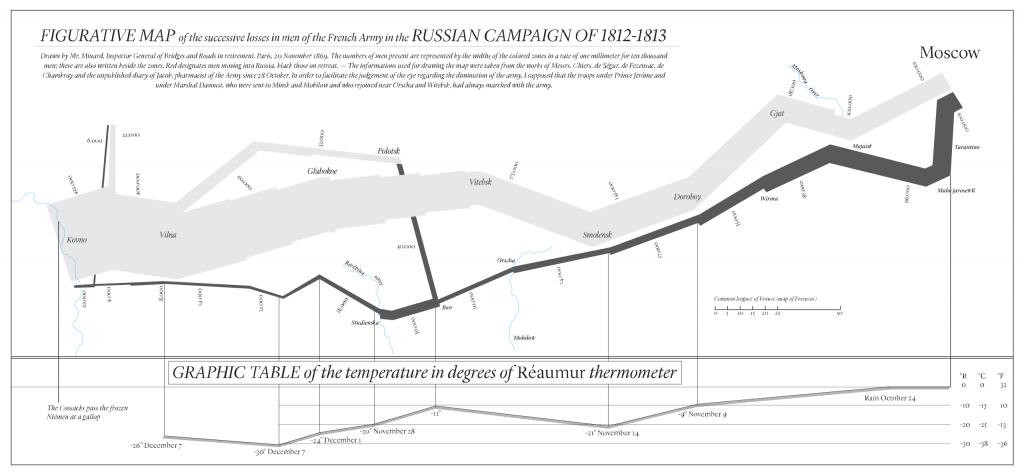

The French retreat in one of the most famous infographics ever produced, by Charles Joseph Minard in 1869. It shows six types of data on two dimensions: the number of Napoleon’s troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates. Lithograph, 62 × 30 cm. This is the modern English translation created by Inigo Lopez Vasquez, available on Wikimedia Commons.

Chapter 19

The French retreat to Smolensk along the road they took to come to Moscow, losing men all along the way. Meanwhile, Kutuzov tries to prevent the Russian army from attacking the French, which seems completely unnecessary.

Book Four, Part 3

Chapter 1

More reflection on the Russian “victory without a victory” that began with Borodino, ultimately based on the fact that the rules and traditions of war were being broken after that point and as the French retreated. Extended simile for the guerrilla warfare that ensued: A fencing duel in which one of the parties throws out the rapier and takes up a cudgel, and wins.

Chapter 2

More reflection on the success of guerrilla warfare and the failure of traditional warfare in this campaign, resulting from the fact that the military strategists that go by the rules ignore the unknown “factor x,” the “spirit of the army,” which behaves unpredictably: it is so low in the French that they can only move as a mass that retreats; it is so high in the Russians that they attack even though they are dispersed in many different small contingents.

Chapter 3

In these contingents, groups of “irregulars,” including partisan detachments and peasants play a major role in destroying the French army piecemeal (1114). We now FINALLY get a concrete example and a continuation of the plot: Around October 22, Denisov and Dolokhov and their group of irregulars find out about a convoy of French cavalry baggage and Russian prisoners that they are supposed to attack jointly with bigger regiments. But instead, they decide to attack the convoy on their own, guerrilla-style.

Chapter 4

As Denisov and some of his ragged men ride through the pouring rain and the mud, a French prisoner (a drummer boy) in tow, Petya Rostov joins them, sent as an adjutant from a German general to keep Denisov from attacking. Denisov is ignoring the message, but delighted to see Petya, who wants to stay with him because he is eager to see action.

Chapter 5

Denisov, Petya, and some of his men spy on the French and witness one of their own, the Russian peasant-soldier and sharpshooter Tikhon, as he is goading them and running through their midst. He was supposed to capture a French prisoner for intelligence-gathering.

Chapter 6

Shortly afterwards, Tikhon joins them, and Denisov, interrogating him, is upset that he has no Frenchman to show for (the implication is that he captured and killed one, but Petya doesn’t quite catch on right away). But when he hears that Dolokhov is approaching, he cheers up.

Chapter 7

Petya, excited to be closer to the action, is concealing that the general he works under has explicitly forbidden him from taking part in any action under Denisov (because in an earlier battle, he had galloped into French fire and acted recklessly). He is in love with war and with all them–like his brother Nikolai earlier, but even more extreme and childish: he tries to give everyone presents, share all his possessions, and begs to be able to “command something” (1125). at the same time, he also empathizes intensely with the little French drummer-boy.

Chapter 8

Dolokhov arrives and Petya is awestruck because he knows about his bravery and also his “cruelty to the French” (1128), which is immediately apparent, as he is dissatisfied with Denisov’s kind treatment of the French drummer boy. They clearly do not see eye-to-eye on prisoners: Denisov wants no one’s life on his conscience and sends all prisoners up the chain; Dolokhov thinks of this as hypocritical (the prisoners are just killed later; why not kill them now?).

Chapter 9

Dolokhov has brought French officer uniforms for disguise, and he takes Petya with him as he spies among the French soldiers in the camp, brazen and never suspected (is his French really that good? why? how?). Petya is even more star-struck and kisses him after he tells him to tell Denisov to be ready to fire “the first shot at daybreak” (1132).

Chapter 10

Petya passes this on to Denisov and is told to get some sleep, but he can’t. He talks to a Cossack, Likhachov, who is also still awake, and asks him to sharpen his sabre. He is sleepy and excited enough to go into a sort of trance where the forest and the camp seem like a “fairy kingdom” where he hears “an harmonious orchestra playing some unknown, sweetly solemn hymn” (1134, 1135), battle music to which he drifts off until awoken by Likhachov and summoned by Denisov.

Chapter 11

Denisov is giving orders all around and then tells Petya, on horseback behind him again begging for a commission, to obey him and not not to “shove you’self fo’ward anywhere” (1136). But as the attack begins, that is exactly what he does: he gallops forward right into the middle of soldiers exchanging shots, and he is shot in the head and dies as the French already surrender. Dolokhov frowns as he sees the dead body (“Finished”) but Denisov turns over the dead body with “trembling hands” and makes a sound “like the yelp of a dog” as he is grappling with Petya’s senseless death (1138). One of the prisoners they rescue is Pierre.

Chapter 12

On October 22, the party of prisoners with their ever-shrinking number of guards and wagons, and their own decreasing number of survivors (only 100 out of originally 33o), is still going forward along with the French army. Platon Karataev is very ill, and Pierre often avoids him and his impending death on the march, just as he ignores the fact that other prisoners are being shot if they lag behind (over 100 of them). Instead, he focuses on the marching, on surviving, convincing himself that “nothing in the world is terrible” (1140).

Chapter 13

Around mid-day on Oct 22, Pierre and the others are still marching on the road, lined by dead animals and people “in various stages of decomposition” (1141-42). He thinks about the prior evening, when he listened to Platon telling a story [apparently one of Tolstoy’s favorites]: an old man falsely accused of murder, later tells his story to a group of fellow prisoners in Siberia, among whom is the man who actually committed the crime. The man, stricken by bad conscience, confesses to the crime, but before the innocent man can be pardoned by the Tsar, he has already died. Platon’s rapturous joy because “God had already forgiven” the innocent man is shared by Pierre. [What is the point???]

Chapter 14

But now the march is interrupted by the carriage convoy of Emperor Napoleon and his marshalls coming through. He sees Platon sitting against a tree, looking at him directly, but Pierre marches on, ignoring the French soldiers who are “talking over his head” and the shot he hears, the howling of the dog that has kept the prisoners company–as do all the other prisoner-soldiers walking with him.

Chapter 15

When the group stops at a village, Pierre eats and falls asleep, dreaming of a teacher he had as a young man showing him a globe made of compressed water drops. When a French soldier awakens him by yelling at him, he almost comes to the point of realizing that Platon was killed but he doesn’t want to face it and falls back asleep. He only wakes up when they are liberated by the Cossacks at sunrise, weeping and hugging his liberators. Denisov and Dolokhov have taken over 200 prisoners. It remains unclear whether they will be killed, with Denisov following some Cossacks who are going to bury Petya.

No Scene: More Reflections

Chapter 16

The narrator describes the further shrinking of the French army, especially after it gets cold after October 28, from 73,000 to 36,000. One of Napoleon’s generals, Berthier, describes the misery graphically, but “no one issued any orders” to Napoleon (1149), and his own stay orders on paper, not carried out because everyone is just trying to save themselves.

Chapter 17

As the French army flees, the Russian army pursues them, and, in one area, when the Russians miscalculate where the French will turn and get to a certain stretch before them, the Russian army forms a sort of gauntlet the French have to pass through. The French try to destroy things along the way, like toddlers, mentioned earlier, who want to “punish the floor against which they had hurt themselves” (1150). Everyone is, again, just out for themselves, including the leaders and Napoleon himself

Chapter 18

Basically, the French are destroying themselves, and the narrator is contemptuous of the historians who have written about this retreat, after Malo-Yaroslavets, and who are just wrong when they talk about Napoleon’s heroism or his marshals’ “greatness of soul” (1151) because they all did the morally wrong thing by their comrades. “There is no greatness where simplicity, goodness, and truth are absent” (1152).

Chapter 19

As far as the Russians are concerned, the narrator knows that they are embarrassed in hindsight because even as the Russian army had the upper hand they lost various battles, at Krasnoe and Beryozina. But he also points out that the French victories in these battles “brought them to complete destruction” while the Russian defeats destroyed the enemy (1153). Partly, the historians (again, so very wrong) have seen “mistakes” because they argue / assume that the Russians were trying to cut off the French and failed. But that was not the plan, except in the minds of a few strategists–it was, in fact, completely impossible for it to happen. The coordination of different parts of the army, the numbers of soldiers, the “cutting off” as a strategy, and the health / climate conditions all made it impossible. Russians soldiers were not to blame for this alleged failure–“they are not to blame because other Russians, sitting in warm rooms, proposed they should do what was impossible” (1154). Instead, the real goal, “to free their land from invasion,” was accomplished by letting the French run away, by the guerrilla warfare, and by the Russian army following the French, ready to “push” should they stop fleeing.

Book 4, Part 4

Scene: With the Rostovs in the Russian Countryside

Chapter 1

Marya and Natasha are in deep mourning, both living with a deep “spiritual wound” (1157) after Andrei’s death. When Marya slowly awakens to her duties (to her household, to little Nikolai) and says she wants to go to Moscow to put her house (not destroyed) back in order, Natasha does not want to go with her, because she is still thinking of nothing but Andrei and of what she should have done and said when he was sick and dying. But as she ruminates, the maid bursts in on her with news of Petya.

Chapter 2

It takes Natasha a bit to understand what has happened, but she then immediately shakes herself out of her own mourning for Andrei to deal with her mother, who is nearly delusional with grief and can hardly understand that Petya has died. Taking care of her mother brings Natasha back to life and lets her heal from her spiritual wound.

Chapter 3

Marya and Natasha bond very tightly over the joint care for the Countess, and a “tender and passionate friendship, such as exists only between women” evolves between them, including a “feeling of life being possible only in each other’s presence” (1163), even as they never talk about Andrei. When Marya leaves for Moscow at the end of January (1813, in other words?), Natasha does go with her, since she herself is supposed to see the doctors about her own health.

No Scene: Reflections about the battle of Krasnoe

Chapter 4

Kutuzov has successfully kept the Russians from more engagements, despite his generals’ eagerness to fight the French, because he is determined to lose as few lives / troops as possible, preserve their energy, and just let the French drive themselves out of the country. The narrator tells us that in this respect, he is at once with the Russian soldiers (many of his generals are not Russians) and is doing the right thing. But at Krasnoe, he is unable to prevent the battle, even as it makes no sense to fight it and even though the generals are really not the heroes and victors they think they are, but “blind tools of the most melancholy law of necessity” (1167).

Chapter 5

The narrator reminds us that Kutuzov was criticized and even reviled in 1812 and 1813 for his decisions, while Napoleon was admired as a “great man,” even among the Russian historians. But Kutuzov had very specific goals, deliberately avoiding confrontation with the French and drive them out of Russia without further battle, because of “the national feeling he possessed in full purity and strength” (1170). He is really the true hero in question (who is hero-worshipping now?)

Scene: Krasnoe, among the Russian Troops

Chapter 6

Kutuzov gives an emotional, but rambling speech at the end of the first day of the battle of Krasnoe (November 5), and although many troops cannot really hear what he is saying, they catch and admire his sincerity and “the feeling of majestic triumph combined with pity of the foe” which “lay in the soul of every soldier” (1172).

Chapter 7

On the end of the last day of the 3-day battle of Krasnoe (November 8), one of the infantry regiments, severely decimated since Tarutino, is trying to settle down for the night and stay warm. The only available hut is set aside for the commander, and the soldiers are trying to use the wattle wall of another as a sort of windscreen around the fire. They are in fairly high spirits, even as one of the sergeant-majors yells at them and lashes out at them for cursing and singing as they set up.

Chapter 8

Despite the exhaustion and the bitter cold, the men are in good spirits and “cheerful and animated” because only those who are “physically or morally” the strongest have survived this long (1175). WE are listening in on a conversation between various soldiers about the pitiful French POWs, the many dead everywhere, about the need to finish off “Poleon” and about the amazing view of the Milky Way. Some of the men from the 8th Company decide to go over a few hundred feet to the 5th Company and their fires.