Monday, August 21

Today, I had to say my goodbyes to Judith and Michael after our weekend together, as they started their workdays. Michael took his bike (he has a 6 km/4 mile commute now) and Judith took me with her to Bad Segeberg in her car, where she works–a quick 20-minute commute by car, about 50 minutes by bus (overland rather than freeway). Her day today didn’t start until 10:15, so we had time for her to show me her office and take a quick stroll at the lake before she dropped me off in the downtown area, where I went for a quick stroll in the usual pedestrian mall area with its little shops. Bad Segeberg is like many of the other small towns we’ve visited around here, but it is distinctive in that it used to be a health spa town (“Bad”) in the 19th century, with lots of sanatoria and promenades. In fact, several large hospitals and medical and psychiatric/addiction rehab centers were started that are still regionally important. (Judith’s work as a therapist and social worker, with special expertise in addiction, ties in with that). But the high density of medical care facilities means that lots of people from out of town spend time here as patients and clients and visitors, so the downtown feels a little less sleepy than many others we’ve seen.

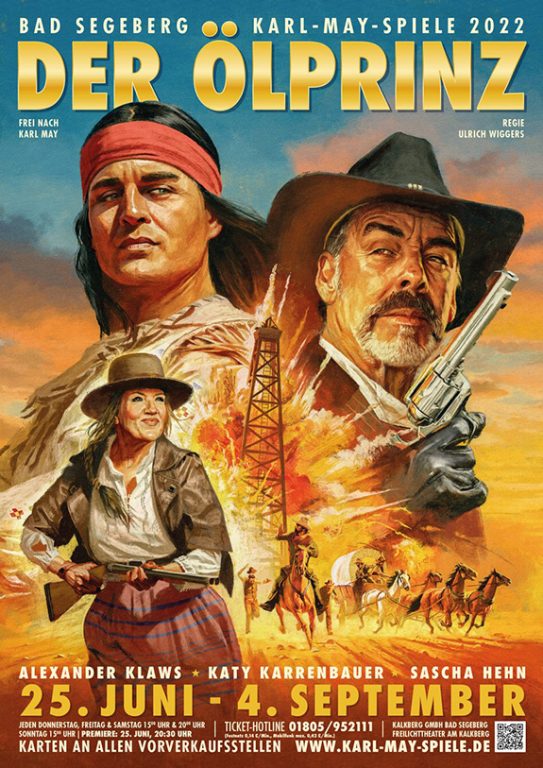

TLDR: The other thing that makes Bad Segeberg distinctive is that it holds an annual summer theater event that is really hard to explain: the Karl-May-Festspiele, which involve simultaneously revolting and fascinating large-scale shows that are basically cowboys-and-Indians re-enactments across a large outdoor terrain (horses, wagons, teepees and all) but always with a storyline based on the schlocky 19th century western novels by a German writer who romanticized Native Americans at the same time as he perpetuated racist stereotypes and white supremacist thinking with a muscular-Christianity / German nationalism flavor that is hard to stomach. Of course course now there is a vigorous debate about cultural appropriation, racist stereotypes, and also the exploitation of the extras and minor actors. And as a cultural phenomenon, it is intriguing and says much about the strange but genuine fascination of Germans (and other Europeans) with what they think is “Indian” that I have always wanted to write about because I totally shared it as a kid. I read Karl May’s novels (dozens of them, over and over again) about an Apache chief named Winnetou and his German friend (May’s wish-fulfillment idea of himself as a traveler and adventurer, “Old Shatterhand”), listened to audioplay adaptations on vinyl records) and watched movie adaptations on TV. But I have never seen the actual Festspiele.

(Not my photo, copyright Karl-May-Festspiele)

Anyway, I took tiny commuter trains from Bad Segeberg back to Hamburg (less than an hour) and was back with Andrea and Peter before 1 pm. We had a simple rolls and cheese meal and Andrea and I took the bus to a nearby park/forested area just for something different, talking about work, life, and the future as we have been throughout my time here. When we got back, I actually had a work-related zoom call (the only one in all four weeks here) and then we met our mutual friend Karsten, whom we’ve known since high school (in fact, he was my high-school boy friend and then my first husband, but that seems like a long time ago—in a great beer-garden style restaurant, Café Strauss, near his house in a different neighborhood of Hamburg (Eimsbüttel). We sampled ostrich meat (the restaurant’s main attraction, Strauss meaning ostrich in German) in the form of burgers, wraps, and salad toppings, and chatted about German politics, our health, and various other boringly age-appropriate updates. Predictably, we also told stories from olden days. It was fun, but I was also very tired when we got back to Andrea and Peter’s after 10 pm.