Thursday, August 18

We woke up quite early this morning (6:30 am) at my sister’s new place and then spent the time after getting ourselves up and running chatting with her over coffee, until it was time for us to take off. We took a leisurely half-hour walk to the center of her village and the grandiosely named “Central Omnibus Station” (ZOB). ZOBs exist in many German cities, typically right by the main railway station and serve as a hub for dozens of different bus lines that start or end at the main station. This ZOB, in a town of not quite 3,000, is actually proportionally impressive in that it has four bus lines stopping (really just two, but in two opposite directions, each of them once an hour on weekdays; very convenient for Judith and Michael, who did not have any bus line at their old place). But it is still a little silly that they actually have four different platforms for this purpose. From the aforementioned bus stop, we took a lovely ride through the countryside with its rolling hills, its harvested wheat fields and hay meadows, and its patches of forest, back to Neumünster (about 30 minutes), caught our train back to Hamburg with ease, had coffee and a snack at the station, and then met up with Andrea and Peter at the nearby Museum for Art and Design (Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, or MKG) in Hamburg.

We’ve been there many times before, but it was wonderful all over again. For one thing, they always have fantastic special exhibitions, and there was one that Andrea and Peter were especially eager to see: the photographs by a photographer named Herbert List (1903-1975), whom I did not know. In the 1940s took photos of an already outdated form of art/science/entertainment: “Präuscher’s Panopticon” at the Vienna year-round fair (the Prater), a cabinet of wax figures (like Madame Tussaud’s but with a weird combination of almost-erotica (“famous courtesans across time”) and anatomical models. Hard to describe, but just up Andrea’s alley, since photography and works with wax and their history are equally central to her own work. There was also a photography exhibit that explored the complex connections between mining metals like silver and photography itself, and an exhibit of seven the museum’s separate collections of individual (typically very wealthy) women’s dresses–starting with a dress and accessories from the 1820s and going all the way to the dresses of the woman who ran German Vogue. One woman, Elke Dröscher, had herself and her daughter exclusively dressed by Yves Saint-Laurent (at least that’s the dresses she donated to the museum), so there were dozens of dresses. But my favorite fashion collection was the only one by an artist, Ines Ortner (born 1968) who made her own outfits in the 1980s, punk-style. One was a dress entirely fashioned out of tabs of pop / beer cans.

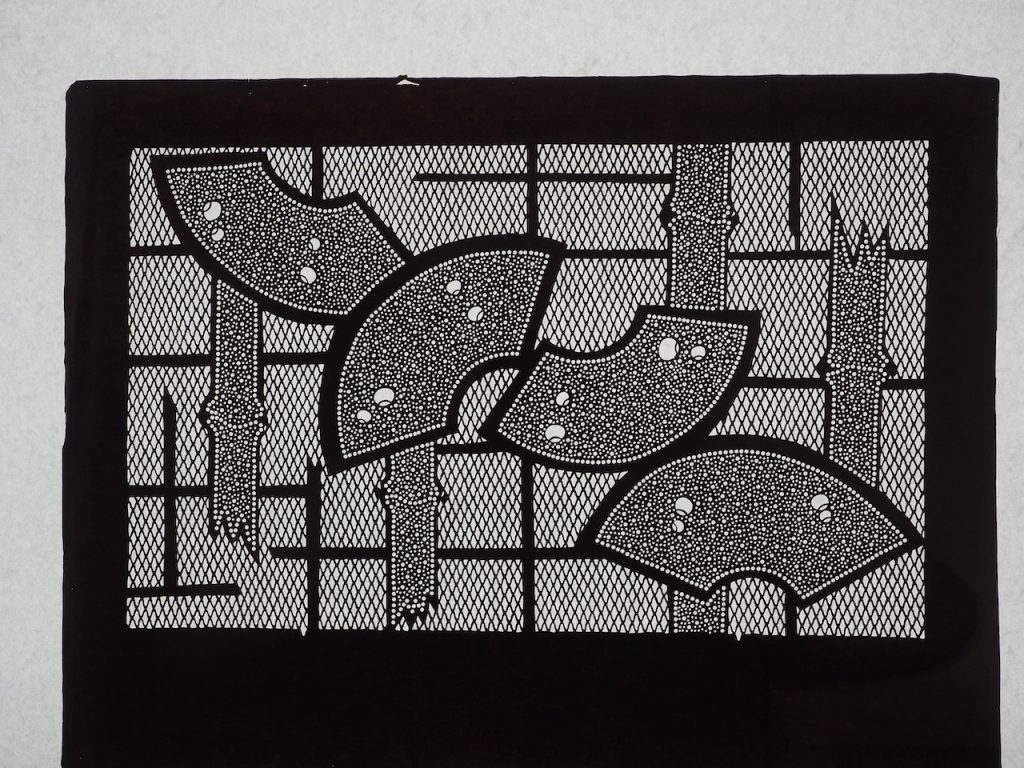

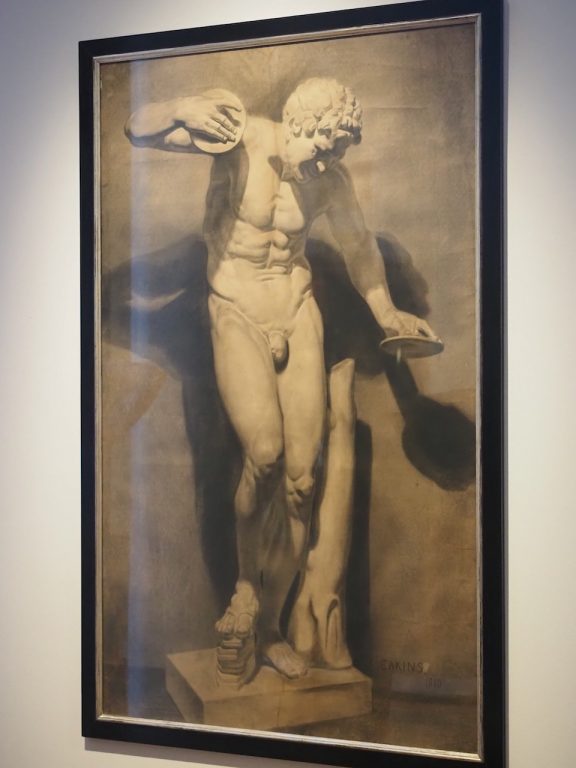

I also went into the permanent collection, because I just can’t pass up their fabulous art nouveau and Bauhaus furniture and dishes. They also have some items by one of my favorite industrial designers, Peter Behrens (“Mr. AEG”), who was one of the very first to design everything for a particular company, from their logos on their stationary to their factory buildings–in the 1920s. There were also unbelievably detailed Japanese paper stencils and beautiful china, not to mention an entire huge hall full of grand pianos–just what you would expect from a giant museum of design. It also brought back many wonderful memories of my history of design course last fall. Since Andrea and Peter both have background in design, photography, and film, this is always one of my favorite museums to visit with them. I always learn so much, even as they make fun of my zipping through the entire museum (or at least HALF of it) while they slowly take in the special exhibits one item at a time. It does make me feel like a terrible art historian, but I am still not very good at standing in front of one work of art for long periods unless I have a special mission. I had Mark photograph only a handful of items, mostly because I wanted to send them to friends; typically, the museum’s website has excellent images and bilingual explanations.

in the entrance hall to the museum

(MATSUKAWABISHI) AND BAMBOO

Katagami Japan, 19th century

We took a break about half-way through our visit to have lunch at the wonderful museum café, the Destille, but I have to say that compared to past visits, their famous salad bar was very lightly stocked and the choices a bit limited. But it was yummy anyway, and we were getting to the hangry point, so the break was much needed.

After our museum day, we returned to Andrea and Peter’s and hung out; it was a good bit cooler today, so it was a very pleasant break from the heat (although still no rain in Hamburg). Andrea and I went to get some groceries and prepared a salad to go with the usual bread and cheese and such, and we had a festive dessert–a classic Hamburg “Rote Grütze,” a kind of thickened fruit compote (think pie filling, not Jello) made with berries and cherries that goes with ice cream or vanilla sauce or sweetened liquid whipped cream, depending on the recipe. I had it with vanilla sauce and was very happy. We also went for a short evening walk right at sunset, although trying to find a good view of the sky and the horizon in a densely built-up city was not really an option. We hope that Andrea and Peter will come visit us next year, and that we can watch sunsets with them from the tenth floor! Mark also did most of his packing, and tomorrow is departure day for him, and we went to bed a bit after 10 pm.